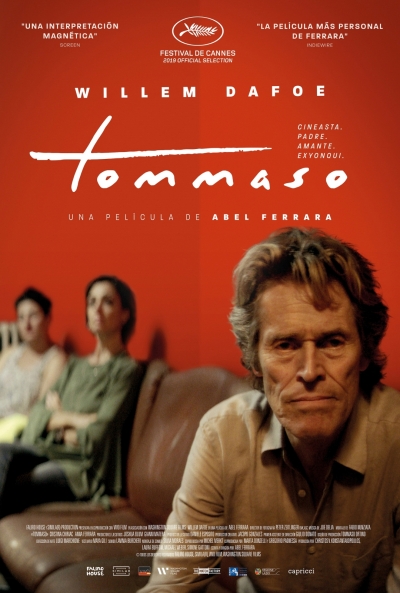

Tommaso [2019] – ★★★★

Abel Ferrara’s Tommaso is a bit of a conundrum from which one eventually escapes feeling even more confused than when first confronted with it. It is a film about middle-aged American film director Tommaso (Willem Dafoe) who lives as an expat in Rome with his much younger wife (Cristina Chiriac) and toddler daughter. He spends his days learning Italian with a private tutor, giving eccentric acting lessons, supposedly writing a new film and going to a therapy in the evening. However, it soon becomes apparent that not all is quite right either with Tommaso or with his present family life that just seems too good to be true. There are bits of greatness scattered throughout this film, and even if Ferrara does not manage to convince us entirely, these pieces, as well as Dafoe’s acting, make Tommaso a very curious film, especially character-wise.

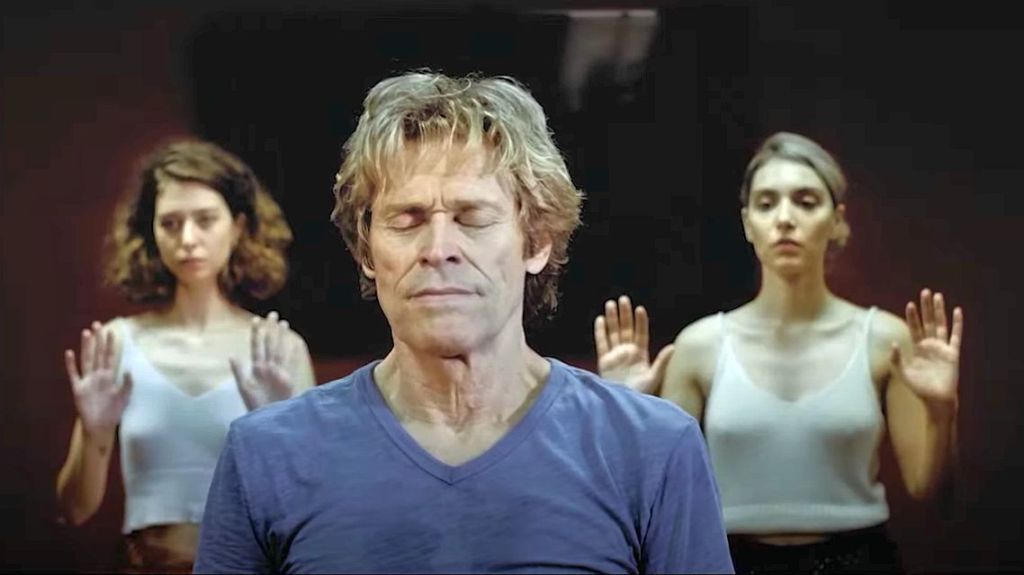

Ferrara’s audience never gets it easy or cut and dry. Tommaso is at times so nonchalant that it seems that it does not care to prove any points, and yet, at its core, there is still some spiritual quest for meaning. Tommaso does meditation and yoga, too in his spare time, and there is a hint that his criminal or drug-addicted past was filled with some multicultural friction. However, we still have to question many things, and the only clearly redundant thing is how painstakingly the director wants to establish Tommaso as this ordinary man wanting quiet family happiness (not without some flirtations on the side) in his sunset years. Dafoe, as an actor of much charisma, skill and versatility, obliges, and this role also follows logically from his previous Rome-based, director-centred role in Pasolini (2014) by, again, infamous Abel Ferrara. Dafoe can be shot in one single room doing practically nothing, and it is still be a film worth watching (as in fact he did in film Inside). Thus, Dafoe’s character portrayal in Tommaso is as multi-faceted and thought-provoking as it can get, and the glaring drawback is that, unfortunately, despite Rome-fuelled nostalgia pretences and odd mid-life desires, Ferrara is still no Sorrentino and Tommaso is no The Great Beauty, and, as the final shots show, Ferrara is also no Scorsese and this is no The Taxi Driver.

Whether Abel Ferrara’s film was inspired by Fellini’s 8 ½ or not (most likely, yes) is beside the point. The film is still a peculiarly Ferrararian concoction: there is the inability to overcome one’s dark past, the main character is constantly looking for “redemption” through suspect ways, and there is also the presence of intense sexual/erotic elements that design to provoke. We are confronted by odd brutality at the film’s end, which is not without its religious reference as per Ferrara, but not before many scenes of intense surrealism and female nudity already left their impression in our minds. Is Tommaso leaving in denial about himself, his present capabilities and his past, we may ask? Is his reality slowly slipping away from him? We are certainly shown many scenes, including dream sequences, which make us believe so. Tommaso’s young wife, their daughter and upscale Rome-setting may just be an idyllic “front” behind which Tommaso hides his own forever-damaged self, past-life’s evil ways and addiction.

In my review of Ferrara’s The Funeral, I said that the director’s characters do not sway between “good and bad” as it is commonly believed, but are actually hopelessly bad “all the way”. They only act or try to act as “good” at times, and Tommaso is that film that again makes this thesis all the clearer. Tommaso is that kind of a man who will kindly surprise his language teacher with a miniature birthday cake or scold his wife for not revealing her whereabouts to him as he is such a caring husband and is worried for her. But, so can the most ruthless and cruel gangster a la The Godfather. An explanation for these acts of kindness may be mere selfishness and the desire to please with future gains for oneself. Throughout the film, we see Tommaso’s adulterous, wayward and controlling nature breaking out, even if Dafoe keeps his character so very humane and sympathetic. Tommaso’s future film’s setting (cold, snowy lands traversed by bears) is in stark contrast to the hot, densely-populated, espresso-drinking Rome he lives in, and this shows that he may be having trouble with the reality that he finds himself in, and if not exactly tries to escape it, then definitely finds issues with it.

Tommaso is probably as misunderstood a film as so many other by Abel Ferrara, but those willing to overlook the director’s usual tendencies towards extremity or odd hard-to-get subtleties (and un-subtleties) will find a film rich in curious main character interpretations and midlife-crisis philosophy.

One Comment Add yours