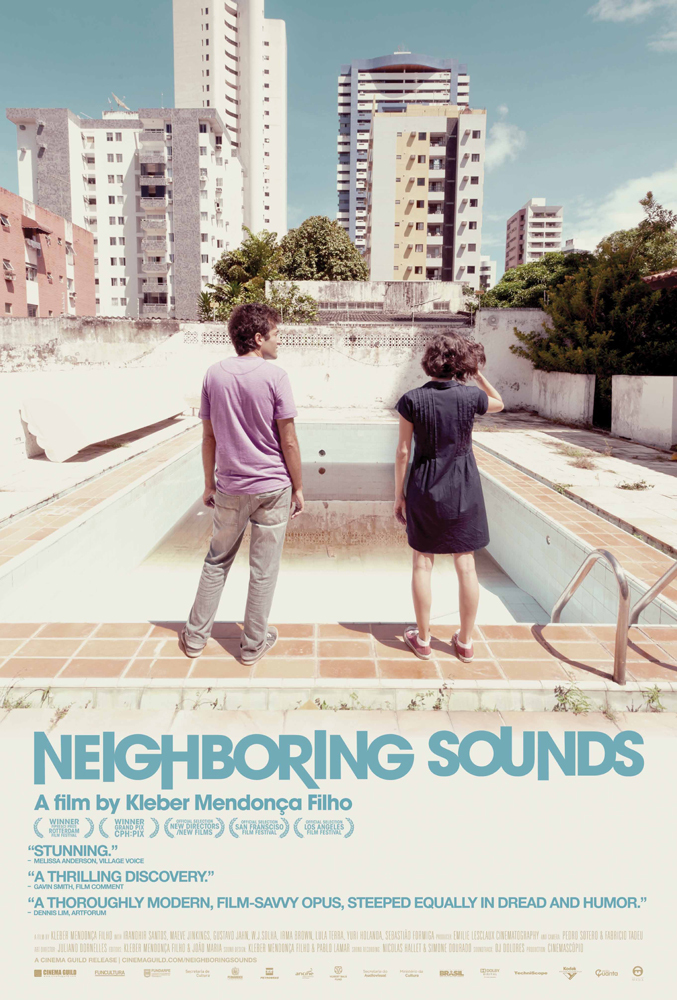

Neighboring Sounds [2012] – ★★★

Kleber Mendonça Filho’s feature debut Neighboring Sounds takes a middle-class community living in Recife, Brazil and surrounds it with noise (even if it is just a howling guard dog) and petty crime (just the other day, a car was broken into and a stereo was stolen). The solution for the people is to hire a private security firm that would take care of their concerns, but that firm soon has issues of its own when their identified criminal, Dinho (Yuri Holanda), is found to have familial connections with the community’s most influential and richest man, Francisco (W.J. Solha). At first glance at least, this seems to be a typical tale of a Brazilian community’s inner-city dilemmas and insecurities echoing urban informality and rooted in living in the proximity of those less fortunate.

In that vein, Bia (Maeve Jinkings), a married mother of two, embodies this community’s middle-class vulnerabilities and anxieties as she becomes oppressed by her neighbouring dog’s barking, also signalling her own marital frustrations. Meanwhile, another resident of the block, young, well-to-do real estate agent Joao (Gustavo Jahn) makes a new girlfriend, Sofia (Irma Brown) who, in turn, takes him on a trip to experience the sorrows of her own childhood home’s thoughtless re-development. This may be a Brazilian middle-class territory, but it is filled with lovers’ clandestine trysts and the delivery of forbidden goods under the guise of innocent home deliveries, such as communal water supplies. So, is the issue for these people the surrounding noise (precipitating in some way hidden violence to emerge, a remnant of the past being slowly re-awakened?). Or, is it, possibly, just the feelings of general anxiety associated with these barely perceivable threats? Or, perhaps, the problem lies in the newly hired security firm responsible for ensuring the peace of all? After all, who guards the guards? Who polices the police?

The film’s deeply observational approach is dictated by Kleber Mendonça Filho’s knack for creative documentaries (Crítico, Pictures of Ghosts), and his seemingly smooth direction establishes naturalism through controlled, provocative camerawork that dissects a segment of society…not in crisis – yet? Most intriguing of all is one dream sequence in which Bia’s young daughter faces her own particular urban fear. But, unfortunately, Neighboring Sounds is still characterised by its sluggish pace that does not fill our increasing need for dramatic purpose, a turn or help find sense in the disconnected dialogues, narrative hints and beautiful images.

The film’s hidden “signs and symbols”, that may be drawing connections between the people’s current urban experiences, noises and Brazil’s past, also hardly convince. Is there somewhere in this work the message that small things represent or form such an essential part of big ones, as, at one point, Joao takes his eyes from the view of urban landscape to look down on a small nut? Or that noise and pleasant sound are essentially one and the same thing, and it is only our perceptions that differ, as in one scene where Bia is at first annoyed by music blasting from another apartment (at first, irritating noise to her), but then comes to enjoy its rhythm (it becomes to her a pleasant sound)? We can only make guesses.

Neighboring Sounds may be suggesting that, symbolically too, noise from usual domestic objects, such as a vacuum cleaner or washing machine, camouflages other more illicit, immoral activities that the middle class engages in (such as Bia’s craving for licit and illicit drugs) – even as that group of people presents the world of respectability and decency to the outside world (represented by Bia’s well-behaved children who take private lessons in English and Chinese). But, even here, the general feeling from the film is the apathy as to whether we will get any of its intended references, intentions or themes, and that automatically alienates us from participating in it fully. The director’s lens cannot be more “real”, but the artificiality of the actors’ interactions only increases our sense of indifference towards this narrative. It is as though we have seen something that only has a semblance of reality.

Half way through, the film does start making some narrative and not just neighboring sounds. The story has finally woken up and one discerning drama emerges, involving working-class Clodoaldo (Irandhir Santos), a chief of the newly-hired security firm, and his intentions regarding his new domain – this well-to-do neighbourhood. Naturally, bossy Clodoaldo’s interplay will involve Francisco, the neighbourhood’s mandachuva. But, is it not something too little coming too little? Now that we have come to the first clear dramatic development (that can also be guessed from miles away), the story ironically does not triumph, but settles for an easy, lazy opt-out. It swings from something too nuanced, stagnant for us to care to something surprisingly bold in its implications, but also new (in terms of a sub-plot) and, therefore, almost irrelevant. The past will come knocking at one’s door, and it is all about power, its abuse and boundaries; the putting up of those barriers, their infringement, their destruction, and who can exercise a greater control. Yes, it is a sure thing here, because isn’t this also what Brazil’s history is all about?

With one foot planted firmly in documentary work, the film’s other one is supposed to be a narrative of some insight. This hardly happens. Even trying to read the film as full of metaphors, the presentation awes as the story sedates. There are images of urban domestic life, alleged threats, anxieties, but the source is hollow, the themes – directionless, a critique of society rooted in a violent past, a class friction – almost too cursory to convince. This is a film of sounds or fears – named, unnamed. Would we care? The final dramatic story turn is almost worth a shrug of our shoulders. Neighboring Sounds is a handsome, but lethargic tale of urban cacophony.