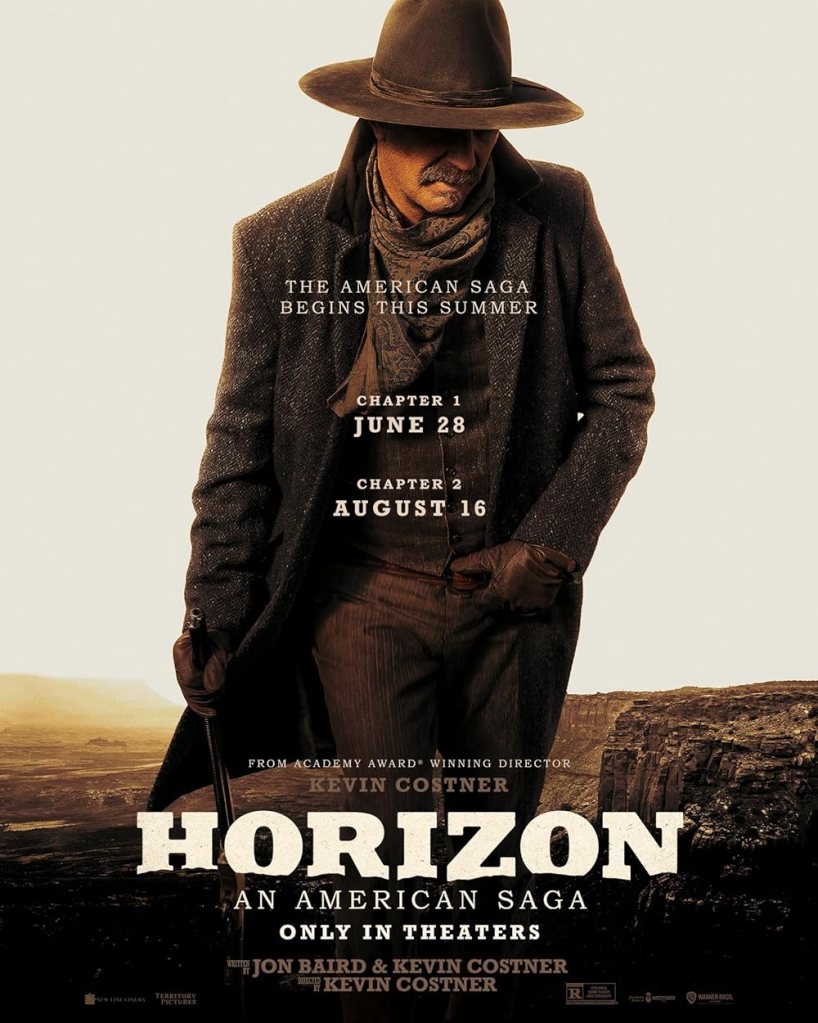

Horizon: An American Saga (Chapter I) [2024] – ★★★★

Costner’s sweeping, imperfect saga is an unapologetic return to the roots and conventions of a classic western.

The enticing, bitter-sweet pull of nostalgia is hard to resist – anyone would agree. And, in a climate where films with original ideas carry a financial risk, directors capitalising on their past box-office hits appear to be making safe bets. So, this year, Tim Burton is back with a Beetlejuice sequel, some 36 years after the original film’s release, Ridley Scott wrapped up shooting Gladiator II (the original film hit cinemas 24 years ago), and the Alien franchise is back (Alien: Romulus). Hopping on this exciting ride of resurrecting past film ideas, Francis Ford Coppola revamped his ambitious passion project Megalopolis, in development since at least 1983, and now Kevin Costner is also seeing his hard-fought, decades-in-the-making story-western brought to the big screen. Horizon is a four-chapter saga that transports us back to the first settlers’ experience of the American West.

John Ford once elevated a western in Stagecoach (1939), and the genre was once “buried-for-good” by a financial disaster that was Heaven’s Gate (1980), before being resurrected by Costner himself in Dances with Wolves (1990). It has since waned in popularity, but those modern westerns that were successful had one thing in common: they did not really focus on the indigenous population (The Proposition, The Assassination of Jesse James, Jauja, The Revenant, The Power of the Dog). This is for a reason. Costner’s retrospective that shifts danger from within a local community back to the historic frontier is then not only courageous, but also refreshing, providing an escape from nebulous, ultra-modern topics that currently flood Hollywood, including robots, AI, and futuristic superheroes.

Horizon’s very first scenes suggest the return to the “good ol’ days” of American westerns. The film opens in San Pedro Valley of Arizona, 1859. Here, surveyors (a father and his son) are mapping out their homestead – a new frontier town, Horizon. Wide shots convey the beauty of vast expanses of land, looking glorious, bathing us in the warmness of nostalgia. J. Michale Muro’s dazzling cinematography captures the sun-lit plains and, then, the tragedy befalling the said father and his son once so eager to settle down in this deceptively peaceful place. The key word is romanticisation. The next image of a lone, aging horse-rider, who battled all weather conditions to finally reach Horizon, as he discovers the bodies of this family of surveyors, is so iconic it could be straight out of any number of past western films. And, to complete the image-painting, John Debney’s “throw-back” music mimics the traditions of past orchestral western scores, conveying the mystery and majesty, and then danger, of the place through delicate woodwinds and a heroic brass.

Screenwriters Jon Bairdand and Kevin Costner decided to go for a multiple perspectives’ account of the Old West, making episodic this three-hour-long chapter. This ambitious structural approach recalls old cowboy anthologies and later popular TV series (Buffalo Bill, Jr., Death Valley Days), and meant to emphasise not individual people, but their different experiences, inter-relationships, actions, and consequences of their actions. This is especially effective in this story that stresses not some character insight, but the never-ending cycle of brutality and revenge afflicting people. And, the violence we see in the film’s beginning does not set out the film’s tone – it is too diffused, as Costner’s scope is so wide-ranging. “Bad apples” have long been inside both camps of the historical conflict, passing the idea of revenge to the next generation, the film implies. Costner may be saying that the way forward is realising our common humanity, but he also conveniently forgets that it were the white settlers who came onto the home territory of the indigenous people, and not the other way around.

So, what is Horizon all about? Unlike what everyone shouts about, there are only three intertwining stories, and though there are a number of characters, a few main ones stand out. One story follows Frances Kittredge (Sienna Miller)’s family, whose homestead in settlement Horizon is attacked by the Apache tribe, led by blood-thirsty Native American Pionsenay (Owen Crow Shoe). Frances loses a husband and son in the raid, but her daughter Elisabeth (Georgia MacPhail) survives, and they attach themselves to the protection of the Union Cavalry headed by Lt. Gephardt (Sam Worthington). There is some growing romance between Gephardt and Frances. So, roughly the first hour of the film is the settlers’ conflict with the Native Americans.

The second narrative line is the experience of Lucy (Jena Malone) as Ellen Harvey who is on the run from the Sykes family after she shot James Sykes (Charles Halford), with whom she co-habited. The brothers Sykes, set on revenge, pursue Lucy and her son, a small child who happens to fall unexpectedly under the care of young prostitute Marigold (Abbey Lee) and travelling horse-trader Hayes (Kevin Costner). So, the second hour is the conflict between the settlers. The third story concerns the journey of a caravan of settlers through western Kansas (the Santa Fe Trail) led by Matthew Van Weyden (Luke Wilson). It is here some out-of-touch intellectuals clash with hardened common folk.

Some scenes do confuse, and the film would have benefited from smoother editing, ensuring better pacing. For example, when the Native American raid happens, it is not clear to where one boy escapes, and then we simply see the Union Cavalry already questioning people in Horizon. Moreover, Lucy’s first meeting with, and true connection to, businessman Walter Childs (Michael Angarano) is never shown or explained, though they are obviously already a married couple. It seems that complex situations emerge in the film, but they are confined to frames and specific running times. And, the dialogues are not “plodding”, as some claim, but simply “thoughtful”, allowing us, the viewers, enough time to inhabit the same space as the interlocutors, integrating us into their environment. Horizon’s imperfections actually charm, rather than repel.

And, then, there is this question – is Horizon revisionist? It may look like it at first, since it subverts the usual western presentation by showing the positions of both Native American people and white settlers in their conflict. However, in fact, Horizon’s very soul is a pure classical western. We see it everywhere, but, especially, in Costner’s refusal to reframe any conflict, stick to the clear demarcation between good and evil, and in the presentation of his characters that emulate the usual classic western stereotypes, those archetypes and clichés that helped popularise the genre back in its heyday.

So, per the classic western genre, Horizon frames women in relation to their men, dividing them into either nurturing motherly figures to protect (Frances, Elizabeth)/romance, or deceitful “femme fatale” prostitutes (Marigold). In fact, Frances and Elizabeth are presented as being so fearful of their surroundings that both almost jump on a bed at the sight of tiny scorpions. The men, of course, are figures of action, being either goodness, reason, and common sense (Hayes), or badness (Caleb Sykes), bordering madness. As per a classic western, Hayes is that gallant, self-sufficient, initially emotively paralysed, man. He is a lonely, aging “rolling stone” always ready, but initially reluctant, to take up arms. Women, such as Frances and Elisabeth, give hope to the men symbolically, and in one scene, Elisabeth even cuts out a flower out of some cloth to give to those men called to fight in the Civil War.

In the tradition of such films as Fort Apache (1948) and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), the Union cavalry stationed at the frontier is the every image of brave protectors ready to rescue at a moment’s notice in Horizon. Costner even reanimates the classic western image of a doctor who is perpetually drunk, being a visibly incompetent man, as epitomised in Stagecoach (1939), and the generational conflict of noble chiefs vs. rebellious youth is also present in the film. This is a usual fare, a workable formula that was expected from the genre back in the day.

A film that feels as out of place in 2024 as Horizon is bound to reap much negativity and misunderstanding, and only a few rewards. But, Horizon’s every shot is still a testament to Costner’s love and devotion for the genre, and this aspect makes the film feel well-intentional. The film has a great sense of place (those exquisite backdrop shots bring out the grandeur of the Western landscape), as Costner also recreates the classic western genre’s elements, such as thrilling chases, gun-fight sequences, and curious, funny situations happening on the wagon route. The director plays this classic card effectively, mining the roots of the genre, and the story engages, romantisizing the action. Injecting any modern sensibilities into the film, including reversing the stereotypes and attacking the characters’ one-dimensional nature, would have reduced the film to being exactly the opposite of what it evidently set out to be – a film in the classic western genre. It is a genre necessarily based on a myth, not some historical accuracy, and has a spectacle and not character-depth at the centre. It is a joy to mentally inhabit this old world carefully constructed by Costner, taking in the multiple perspectives.

The director also gives a sufficiently dignified performance as drifting, “no-nonsense” horse-trader Hayes Ellison, but he is a far cry from the warm charisma of John Wayne or the stoic, mysterious, arresting presence of Clint Eastwood. Only Costner is not really the leading man in Horizon (Chapter I). The 69-year old actor may have massaged his ego when young, beautiful prostitute Marigold (Abbey Lee) demanded some attention from him in the script, but can a film really be an actor’s ego trip when his screen-time is so comparatively modest? We do not even see Costner until at least an hour into the film. A classic western’s success is partly defined by its main character’s centrality, and when Horizon overturned this rule, we can only guess at this point what would be the final result. Lee’s own character, prostitute Marigold, gives off a peculiar 21st century sense of irritable frivolity and comical theatricality, as though she was taken straight from the Friends set and unwillingly thrust into this historical drama. So, the interactions between Costner and Lee raise some eyebrows, but the villain camp does much better, such as Jamie Campbell Bower, who becomes the embodiment of psychopathic villainy. The cast of Will Patton, Danny Huston, and Luke Wilson is a nice surprise, too.

The final scenes of Horizon: An American Saga (Chapter I) is the rapid montage of some scenes from the two chapters with a score. Will Hayes ride off into the sunset in the final film, another staple of a classic western that represents finding peace and harmony? I guess we will find out in Chapter 4.

All in all, intentionally and necessarily retrospective, and unafraid to rely on long-forgotten classic western archetypes, Horizon awes as a steadfast, beautiful, and exciting tribute to one old, buried-under-fifty-feet-of-mud Hollywood genre. In our progressive, enlightened year of 2024, there are no pretences that this film series could be anything but a wistful, one-off love-letter to the cinema of the past, and it is certainly not the revival of some trend or cinematic direction. Horizon simply entertains as any good, multi-layered adventure film would, romanticising historical myths embedded in American cinema and simply wallowing in nostalgia as it recalls the genre roots.

An excellent review. I wasn’t planning on seeing this movie but your review has compelled me to check it out. I’m a big fan of westerns and adore the films in this genre. The premise for “Horizon: An American Sagal reminds me a lot about Clint Eastwood’s classic westerns from the 1990’s. For instance, the story of the film is very similar to “Unforgiven”. I really loved “Unforgiven” which is one of my favourite westerns of all time. So, I’ll definitely check out this movie when I find the time.

Here’s my thoughts on “Unforgiven”:

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s surreal seeing a western in 2024, but I’m not surprised Kevin Costner would be involved given his filmography and his recent success with the Yellowstone series. I can’t lie that it’s not my favorite genre and seeing things about someone like John Wayne (his movies and himself in real life) really didn’t help. However, it’s fascinating when people deconstruct the genre or make hybrids like space westerns (Outlaw Star, Cowboy Bebop, Firefly), Theeb which was a Jordanian take on the genre, or meat pie Westerns in Australia such as The Tracker.

LikeLiked by 2 people