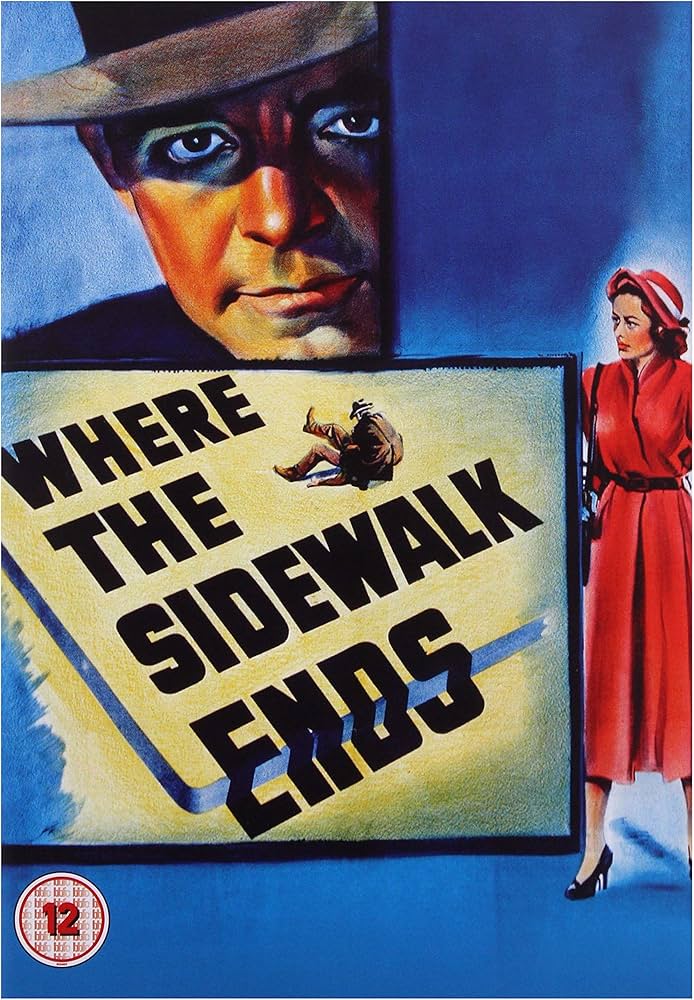

Where the Sidewalk Ends [1950] – ★★★★

Otto Preminger was one of those directors who were never afraid to tackle controversial topics in film, pushing the boundaries of censorship. He dealt head-on with such topics as addiction (The Man with the Golden Arm) and rape (Anatomy of a Murder), challenged the presentation of women’s “hysteria” (Bunny Lake Is Missing) and exposed an American political process (Advise and Consent). And, all while most other directors of that period had barely even tried to approach these taboo topics. And, while Where the Sidewalk Ends does not really deal with any glaring controversies, it still presents an uncomfortable image – a violent and out-of-control member of the law enforcement, and that some twenty to forty years before this seedy archetype would take deep root in Hollywood, for example, in Abel Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant (1992) or in Sidney Lumet’s films Serpico (1973) and Prince of the City (1981).

Where the Sidewalk Ends is based on William L. Stuart’s 1948 novel Night Cry, and is about New York City’s Police Detective Mark Dixon (Dana Andrews) who has a history of dealing roughly with criminals and members of the public, and has already received a fair share of complaints from civilians because of his behaviour. “Your job is to detect criminals, not to punish them”, Dixon is told by his superior. When Ken Paine (Craig Stevens) and his ex-wife Morgan Taylor (Gene Tierney) attend a gambling event, another man there refuses to pay the money he owes and ends up dead. According to Dixon, he could have been killed by either gangster Tommy Scalise (Gary Merrill) or Paine himself , who were both present at the scene.

When Dixon goes to question Paine, an altercation occurs between the two, and, soon, Dixon’s “history of violence” means that he can no longer escape from being entangled in crime, deceit and manipulation, especially when he also grows close to Paine’s ex-wife, beautiful model Morgan, who also has a touching relationship with her father, taxi driver Jiggs (Tom Tully). The fate of this man, Jiggs, will hang in the balance as Dixon considers how to cover up best his unfortunate encounter with Paine that saw that man also falling dead.

One of the themes of the film is the “history of violence” and what it does to people, as well as the question: what makes a criminal? Is it nature or nurture, or, perhaps, something else? Dixon’s father was a hardcore criminal and a thief. Can Dixon’s propensity to violence be explained by his upbringing or genealogy? Dixon’s cynicism and violent impulses not only let themselves known once again when he interacts with Paine, but Dixon’s previous history of violence known to his police department means it is not so easy for him to then confess to his subsequent action and face consequences.

Such 1950 films as In A Lonely Place and Gun Crazy are further examples of that year’s cinematic obsession with a character’s criminal past, and its present consequences. If the former film was all about questions whether a man’s temper can really point to him being a murderer, the latter film showed how a girl with a criminal past could implicate her man, who was previously averse to violence, in the same dangerous activity and only because that man happens to have an obsession with guns. On that basis, it seems at first that Where the Sidewalk Ends may be another socio-economic character study, that of Mark Dixon, but it is not – well, not really. Elements of a crime and the evolving intricate plot soon take central stages in this film, with enough thrills and turns to keep the audience entertained – until about the second half.

Prolific actor Dana Andrews does capture the moral dilemmas of his character well, especially with his facial expressions and dialogue. Tierney (Leave Her To Heaven), on the other hand, is a rather distant, predictable Morgan Taylor, full of charm, but also airs, making her a believable femme fatale, but hardly a sympathetic person that just decided to side with an underdog. The supporting cast also shines, including Karl Malden (A Streetcar Named Desire) as Dixon’s boss Lieutenant Thomas, and Gary Merrill as ruthless-to-the-point-of-lunacy Scalise, the head of a criminal gang. The veteran of black-and-white cinematography Joseph LaShelle (The Apartment, Marty), who, in his career, would go on to be nominated for some nine Academy Awards, further lends this film the necessary aura of explicable mystery and broodiness, with more than a few shots even reminiscing Fritz Arno Wagner’s work in Fritz Lang’s M.

Francis Ford Coppola once said of Akira Kurosawa’s film The Bad Sleep Well (1960) that its first thirty minutes were as perfect as any film he had ever seen. This verdict is perhaps equally applicable to Where the Sidewalk Ends. It is only in the film’s second half that we see an unfortunate disintegration of its tightly-constructed plot, a plot that in its first half could have equated Preminger’s cinematic masterwork Laura. Where the Sidewalk Ends’s second half starts to have plot holes and there are also misguided attempts to elicit sympathy for Dixon. Here, it is not longer the ingenuity of the plot or the pacing of this thriller that become important, but the melodramatic relationship between Morgan and Dixon, whose attempts at redemption just raise eyebrows.

Lieutenant Thomas’s investigation into Paine’s murder was apparently so good and hit so many right spots that it was great news for the victims and for our sense of justice, but also necessarily robbed this film of much suspense and intrigue. The ending is almost anti-climatic in its nature as the film loses its sense of conviction, adamant to have its A Place in the Sun (1951) ending. Though perfectly fine by the standards of its day, this is surely not what the modern audience is expected to witness, spoilt by all the gloomily shocking finales of more recent cinema.

We can detect in Where the Sidewalk Ends some faint, distant thematic echoes that would later become loud and clear in such films as Dirty Harry (1971) (Inspector Callahan’s portrayal) and A History of Violence (2005). That means that the film’s quiet, barely perceivable influence exists. And, while Where the Sidewalk Ends is known for being compared negative to Preminger’s Laura, this comparison is not altogether just. Laura was based on a masterwork of a book, Vera Caspary’s slim novella of much hidden power and curious psychology that also contained an unforgettable twist in the middle, and the main narrator, an eccentric man, constantly leading us astray. Arguably, in Where the Sidewalk Ends, Preminger did his best with Hecht’s script and Stuart’s novel at hand, works that certainly do not grab the audience in the same way as the final unravelling of Laura. So, as it stands, though Where the Sidewalk Ends wanes in its intrigue and believability in the second half, its thrillingly clever beginning, palpably gritty nature, and the galvanising acting still make it a memorable viewing experience.