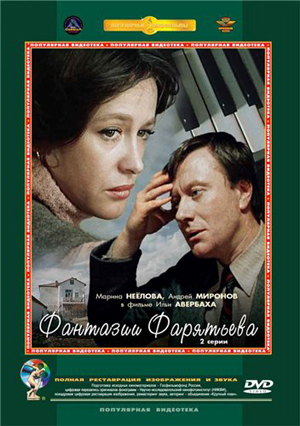

Faratyev’s Fantasies [1982] – ★★★★

Soviet director Ilya Averbakh (1934-1986) was first a doctor, having finished a medical degree, and only then a director, and perhaps that is why many of his films are characterised by certain exactness, almost medical precision, and clarity of vision. They also lean towards Chekhovian pathos (incidentally, Chekhov was also a doctor first), and try to distil the tragedy of individual life full of intellectual pursuits, sensitivity and soulfulness vis-à-vis daily brutal realities surrounding it.

Averbakh’s Faratyev’s Fantasies is based on a play of the same name by Alla Sokolova, and is a searching, moving account of three generations of people trying to understand themselves and each other in a span of few days in Feodosia, Crimea. Dentist Pavel Faratyev (Andrey Mironov) is a day-dreamer, an idealistic man desperately in love with seemingly cold and distant piano teacher Aleksandra (Marina Neyolova), whom he met just ten days ago at a birthday party of one man Bedhudov. Disillusioned in her own private life, Aleksandra is apathetic towards everything, and views Faratyev’s romantic advances with annoyance one day, and friendly sympathy – another.

Their societal microcosm is shared by Aleksandra’s controlling mother (Zinaida Sharko), who only wants to marry her daughter off as soon as possible, and Aleksandra’s bratty, headstrong and loud-mouthed teenage sister Lyuba (Yekaterina Durova), who represents the new Soviet generation already rebelling against the conservative norms of their parents. In turn, and at the other end of the spectrum, is Pavel Faratyev’s aging, lonely aunt (Liliya Gritsenko), who is the most sensitive, delicate and cultured person in the story, supporting unconditionally her eccentric nephew in his “grand work of ideas”.

Rather than trying to go beyond the confines of the play, Averbakh’s direction seems to emphasise it in every frame, doubling down on all theatrical effects, and, surprisingly, it is not melodrama and over-sentimentality that overpower the audience, though both are present to an extent, but much nuance and profundity. That is thanks to the play itself and the acting.

The film opens with a private piano lesson given by Aleksandra to her pupil, a little hooligan boy. The imperfect notes of Czerny’s etude resound through the room, establishing Faratyev’s repeated theme of dissonance, cross-purposes and misunderstanding. Faratyev is present during the piano lesson, sitting gloomily, and foolishly trying to talk with Aleksandra about the weather, and how she spent her weekend. All in vain, Aleksandra is polite, but uninterested. Their uneven relationship is underscored by her commanding, authoritative demeanour towards the little piano student. Faratyev’s head-in-the-clouds attitude clashes violently with Aleksandra’s realism. But, she is not just passively dismissive, she is thinking of other things constantly – things that do not concern or include Faratyev. That is the main idea of the film. We all live in our own worlds of thoughts and feelings, and expect others to share some of them wholeheartedly – but, most likely – they do not – because they have their own worlds, being caught up in their own mind-games and private desires. And, that is painful because we care. The way the film brings this idea forth is through the delicate seeping into our mind (scene by scene, monologue by monologue), rather than through one grand gesture, and that makes the film powerful in its understatement.

Aleksandra clashes with her overbearing, self-pitying mother over Faratyev’s marriage proposal, and then, reluctantly agrees to it. Her sister Lyuba throws fits of youthful rebellion, while Faratyev retreats into his idealistic world where people are never alone, but “overseen” by other people living in other galaxies – one of his theories. His aunt, also deep in dreams and their significance, shifts to realism the moment she realises that Faratyev’s marriage may fall apart because of his eccentric ideas (Aleksandra’s family may deem him “too crazy”). Everyone has their own vision of life, happiness and future and tries to “impose” it on another. The inner world of feeling and the outer world of reality are constantly fighting for dominance. The film becomes a series of monologues where people make speeches and respond, but never really listen or understand one another. And, when people do understand each other, it is the “wrong” people who finally understand them, the ones that were not the prime targets of all the pleas or discourses.

Ordinary domestic banter gives way to philosophical musings on the meaning of life and existence. “How do you escape this magic circle? We are not bad people, we want the best for each other…why are people torturing each other so?”, asks puzzled Aleksandra at one point. If her room is full of music (she is a piano teacher), in Faratyev’s household, we often hear the loud ticking of a clock that perhaps signals Faratyev’s dreams slipping away, emphasising how little time he has to play with them before the brutal reality comes knocking at his door again. The clock ticking unsettles, but also transports us beyond the stuffy rooms to dreamy realms inside the minds of Faratyev and his aunt (the ticking clock was used most effectively in the dream sequences of Rosemary’s Baby (1968)). “Dreams are dreams, reality is reality”, says Aleksandra to Faratyev sometime later, but this is of no use – one’s dream is one’s reality. The name of mysterious Bedhudov functions in the story as a wake-up call for everyone to come back to reality and rise from their collective trance. It is on par with the name of Rebecca from Daphne du Maurier’s novel – a powerful connotation, the answer to everything, but dropped so casually here and there, and the named person remains always hidden, never appearing in the actual story.

Ilya Averbakh could not have had a more talented cast to play out the psychologically intense drama and bring out the true magic of the play. The ever great Mironov, one of the best actors of his generation, takes to the role like a duck to water, shining with great conviction and eliciting much sympathy, while emphasising his character’s deeply emotional and intellectual worlds coexisting with his outward awkwardness and foolishness, as perceived by others. His scenes are hypnotising, and the light going out of his character’s eyes in the second half of the film is, to us, the end of the world. Zinaida Sharko as Aleksadra’s mother brings much energy and personality to contrast wonderfully with the more reserved and dignified performance by Liliya Gritsenko, Faratyev’s aunt. Yekaterina Durova plays a somewhat one-sided Lyuba, but she soon reveals hidden layers to her character we never even suspected.

A more imaginative camerawork, lightning or scene design/sequence would have probably made the film grandeur in certain respects, but, paradoxically, its visual restraint only underscores the power of the core acting, as well as the original play’s emotion and intellectual thought. At the end of the film, we are back at the beginning, but the world will never be the same again. Faratyev’s Fantasies simply strikes a chord. Our hearts and minds respond instinctively to the topics raised. Isn’t that what cinema should be all about? And, this is also a film that undoubtedly “improves” on multiple viewings because it has enough “blank spaces” (the character’s silences, quiet gestures and stillness after thought-provoking discussions) for us to want to fill in the void with our own reflections – and do it again and again. It is a setting no audience wants to leave. If the film’s point is that people are often quite unable or unwilling to understand one another, we can at least take comfort in the fact that the film understood us.