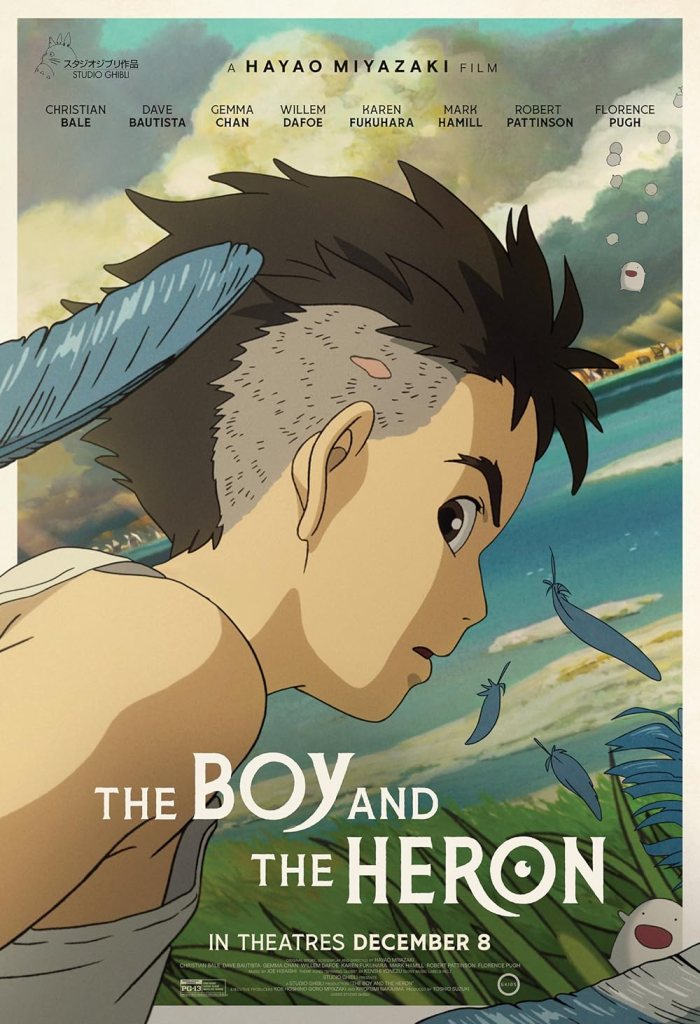

The Boy and the Heron [2023] – ★★★★1/2

🦜 The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki’s “fever-dream”, a symbolism-driven animated tour de force.

“What drives the animation forward is the will of the characters”, once said Hayao Miyazaki. The Boy and the Heron, which is to be the great Japanese director’s final film, encompasses plenty of that will to understand, overcome and accept. The story is set in war-time Japan, and focuses on sympathetic boy Mahito, whose mother tragically died in a hospital fire in Tokyo some four years previously. He goes to live with his father in the countryside, trying to get used to his new home and his step-mother/his aunt. However, Mahito is bothered by strange visitations from one heron, and when he suffers a head injury and his stepmother mysteriously disappears, he embarks on an unfathomable rescue mission. The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki’s most metaphorical animated film to date, a bitter-sweet adventure story that, in a nutshell, portrays a bumpy road in trying to come to terms with one’s traumatic past.

There are really two ways to view The Boy and the Heron. One is a straightforward story about a boy on a journey to the “underworld” to rescue his new mother from peril, and another is a tale of metaphors about a boy who is trying to overcome his grief regarding his dead mother, accept that circumstance, move on and learn to live in this world that is also the place of evil and death.

On the surface, the story is a typical “rescue adventure” hero’s journey where the boy tries to locate his stepmother while encountering both resistance and assistance along the way. It is a sort of an Alice in Wonderland journey, where the boy with a head injury and probably delirious falls into a rabbit hole, and, rather than chasing the White Rabbit, chases the Heron instead.

Under its surface, however, The Boy and the Heron is more complex, and its visual playfulness hides serious topics. The film attempts to show Mahito’s subconscious processes as he still grieves for his mother and tries to understand the role of his “new mother”. The appearance of a heron in Japanese folklore is tied to spirits and death, and is also a link to another world. That is the first sign. Mahito’s step into the realm of fantasy happens when he hurts his head, and from then on, hears the heron speaking a human language. It is at this point that Mahito is transforming himself to become a part of the new world that awaits him – the underworld with its own rules, but also semblances of the real world.

In this sense, the boy’s cautious exploration of the dark corners of the abandoned tower on his stepmother’s estate also means the exploration of his own repressed fears, desires and guilt – the guilt that he was unable to somehow save his mother from the fire that engulfed her and sealed her fate. To overcome something, then, what one first needs to do? To learn about one’s opponent – the nature of death, in this case. In the world of the dead, Mahito learns about it by dissecting a corpse (even if that of a giant fish) and digging a grave (for one dead heron), and all this happens not far from the cemetery island that was undoubtedly inspired by Arnold Böcklin’s painting Isle of the Dead.

The Boy and the Heron assembled the core elements of Studio Ghibli’s previous coming-of-age films: the wonders of nature (My Neightbour Totoro), the pains of adolescence (Whisper of the Heart) and the struggles to become independent (Kiki’s Delivery Service). The trope of a chosen boy with a scar on his head who is there to come to terms with the death of his parent while also trying to rescue one girl (and being friends with an older sage or wizard), may remind of another famous story that was penned by author named J. K. Rowling (Harry Potter & Chamber of Secrets, of course), and though the connection is interesting, it is still purely fun and trivial, rather than obvious.

As in Spirited Away, where Chihiro took the role of an apprentice in a bathhouse, The Boy and the Heron also makes an emphasis on the importance of becoming an apprentice to a more knowledge older adult to learn about the world and overcome hurdles. That person in The Boy and the Heron is an easy-go-lucky female sailor/pirate named Kiriko whom Mahito helps with the fishing. Later, Lady Himi, a girl who can control fire by her mind, does much for Mahito so he can overcome and come to terms with fire being the reason for his mother’s death. Fire is not something to be feared or detested, it can be controlled and “made peace with”.

And, as in Miyazaki’s other films, evil in this story is elusive, imperfect and not what it first appears. In Spirited Away, evil sorceress Yubaba is constantly made fun of, and in Howl’s Moving Castle, the main antagonist, Waste Witch, is soon rendered weak, pathetic, and in need of help and protection, which is also given to her. Similarly, the Heron in The Boy and the Heron can be viewed as this initial antagonistic force that was eventually befriended and even helped out. In Miyazaki’s films, the true opponent is oneself that is yet to see one’s true capabilities and understanding of the world. Humour in the animation is injected through various eccentric characters, including warawara, lovable souls-to-be-born in the underworld, and perpetually-in-need-of-tobacco old ladies in Mahito’s real world.

The film gives itself fully to the wondrous and the unexpected. In fact, there are many scenes of intense and entrancing surrealism, and the final act tries to contain within itself the meaning of the universe and one’s place in it, being as ambitious in this regard as Soul or even 2001: A Space Odyssey. The film’s initial stark realism takes too much of the screen time and sits rather oddly with the completely whimsical and fantastical final stretch. However, Miyazaki’s visual brilliance is there, the passage from one world to the next is still rather nuanced, and Joe Hisaishi’s moving score adds much poignancy to the increasingly complicated story.

“Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood” (Marie Curie). The Boy and the Heron is one’s journey to understanding one’s place in the world, coming to terms with one’s past and moving on. Its rushed, rather confusing final act may raise a few eyebrows, but the overall result is still one of awe and mastery. Miyazaki’s final adieu is full of adventure, wonder and insight.

Great write up. I have not seen this yet and enjoyed your summary, and analysis of the psychological intricacies. I learned that the heron can symbolize the spirit world.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That quote from Marie Curie in the last paragraph is great too!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! I hope you enjoy it if you decide to watch it. As in many Miyazaki’s films, there are layers here, too. Of course, each viewer’s perspective is different, but I just thought that here especially, from all other Studio Ghibli films, there is much going on beneath the presented images – I think that’s also because Miyazaki is also the scriptwriter now. Certain sequences even reminded me of Satoshi Kon.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This could be a good watch. Even though I think Miyazaki is slightly overrated (I’m more of a Takahata guy when it comes to Ghibli), it does look like its worth watching. It also blows my mind that they got a former WWE World Champion to act in the dub. Haha!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I am myself much more of a Kon and Takahata viewer than Miyazaki, largely because I shy away from that kind of fantasy that Miyazaki tends put to the front of his films. However, because the fantastical elements in the Heron can be interpreted in a symbolic way, realism doesn’t suffer in the process, and I enjoyed it. I would love to hear your opinion of the Heron if you decide to watch it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sure thing and I’m the same way with Kon even though he only made movies with Madhouse (not a bad thing of course). I hear what you mean with Miyazaki films. They aren’t bad, but I felt that Takahata was the more interesting director and animator with the Ghibli stuff I’ve seen with Grave of the Fireflies, Princess Kaguya, and even My Neighbors The Yamadas which is an overlooked and funny film. Heron is something I do want to see. If I ever review it, then you will definitely know.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I agree. I have actually seen My Neighbours The Yamadas only recently and found it funny. It is based on a manga, but it also reminded me of post-war comic Sazae-san, which is about a freedom-loving, eccentric woman who broke traditional Japanese stereotypes and made fun of strictness in Japanese interactions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice! I’m glad you’ve seen that movie. I’ve heard of Saze-san, but never checked it out. Thanks for the recommendation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I saw it shortly after it was released. It’s a lot to take in one viewing. Need to see it again. Good review!

LikeLiked by 1 person